Who was Vahe Ihsan?

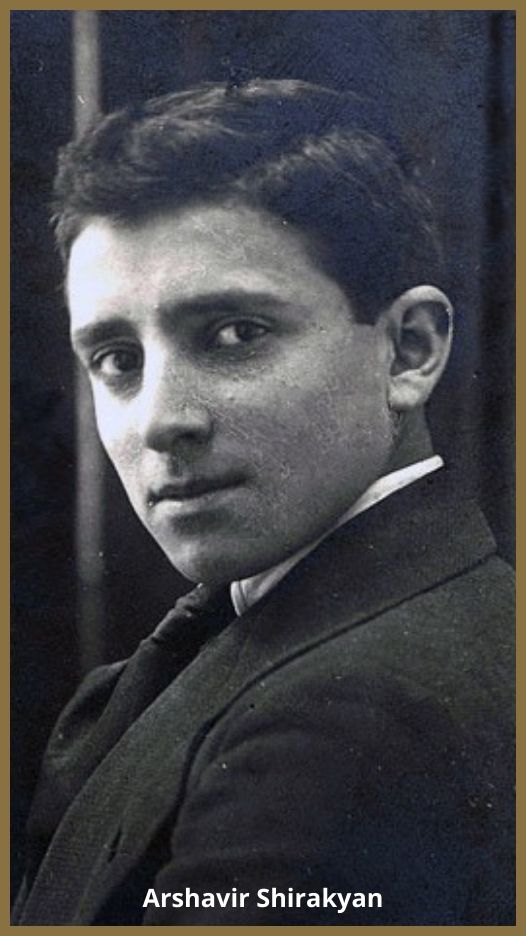

It is known that a number of Turkish and Azerbaijani officials were punished during the Nemesis Operation. However, few people know that several Armenians also received their punishment during the Nemesis. Those Armenians were punished for cooperating with the Turkish police and assisting in the implementation of the Armenian Genocide. One of them was Vahe Ihsan or Yesayan. Not much is known about him. The key information about Vahe Ihsan is derived from Arshavir Shirakyan’s memoirs. As Shirakyan personally executed Vahe Ihsan’s punishment, his memoirs are central to understanding Vahe Ihsan’s character.

Shirakyan describes Vahe Ihsan as a “monster with an Armenian name” who, during the First World War, did not stop roaming the streets and searching the houses of Armenians either alone or accompanied by Turkish police. From the very beginning of the First World War, the course of the Armenian Genocide was clearly outlined, and the Turkish police needed to keep under constant control the events taking place among the Armenians and any more or less prominent Armenian. According to Shirakyan, more than 300 Armenian agents and traitors helped the Turkish police in this endeavour. Vahe Ihsan, a “black-souled Armenian” defined by Shirakyan, had an important place in this group of Armenian agents. He personally accompanied the Turkish police during the searches of the homes of Armenian students and intellectuals. It was evident that he had a high police rank because he spoke in a commanding tone to the Turkish policemen who were with him. Once, he even slapped one of the Turkish policemen on the street in front of Shirakyan’s eyes for an incompletely performed search of the house of an Armenian.

Vahe Ihsan was not only involved in his treacherous activities during the First World War, but he also continued them after the Armistice of Mudros. At that point, he became an agent for the Kemalists. He provided them with a list of names of Armenian revolutionaries and intellectuals, helping the Kemalists to arrest these individuals upon their entry into Constantinople.

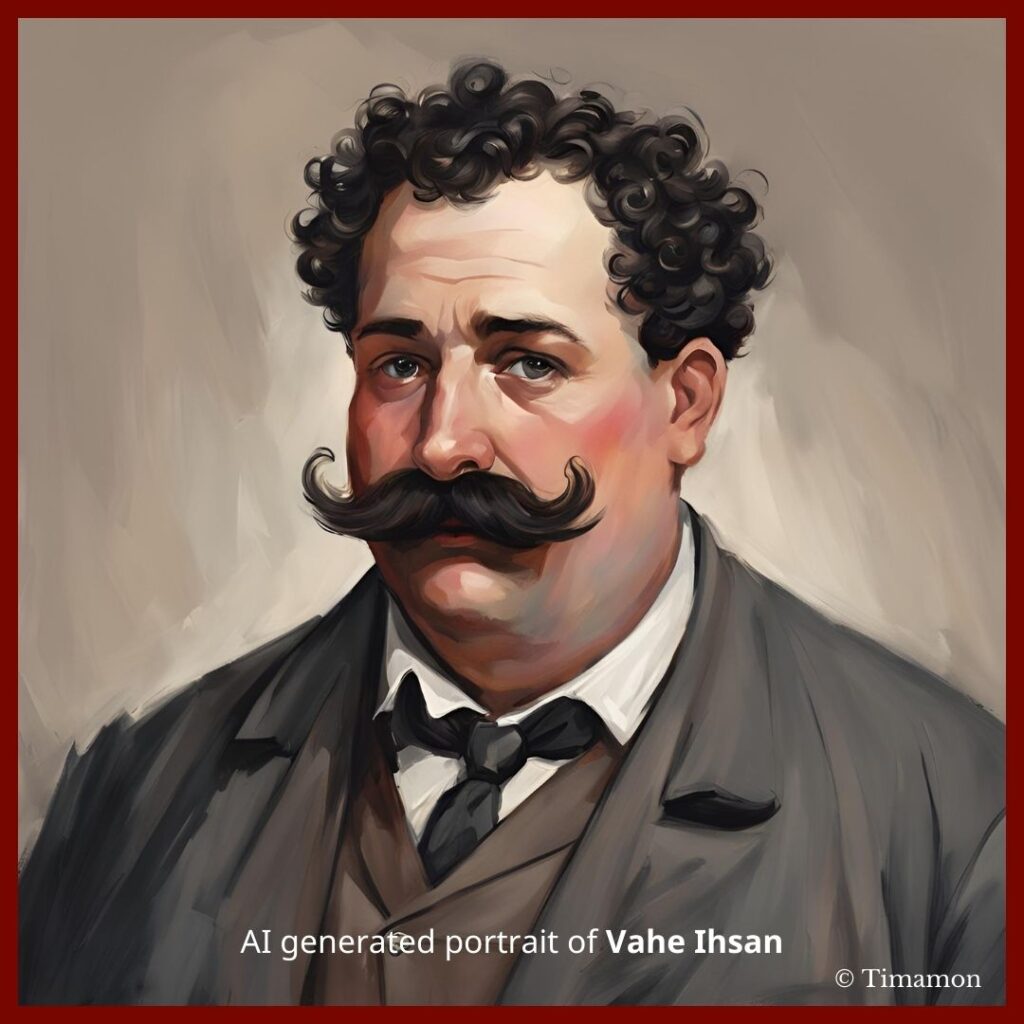

The Portrait of Vahe Ihsan

In his memoirs, Shirakyan describes Vahe Ihsan as “a tall, slightly pot-bellied man with light red cheeks, a black curly moustache, and beautiful black eyes that looked at you with a sneaky and suspicious gaze, similar to that of a Turkish secret or official police officer.” Unfortunately, there is no known photograph of Vahe Ihsan, and it is unlikely that one has been preserved. Nevertheless, it is crucial for us to imagine the traitor’s face vividly. When we think positively or negatively about someone, we first picture their face in our minds. If we cannot visualise someone’s face, we tend to say, “I don’t know him.” However, we are obliged to know Vahe Ihsan. Not knowing him and those like him could be extremely dangerous.

For this purpose, we entered Shirakyan’s description of Vahe Ihsan’s appearance in one of the popular artificial intelligence (AI) programs and tried to get his portrait. Of course, it is difficult to confidently assert that Vahe Ihsan actually had this very face looking at us from the picture. However, this is the picture AI generates based on Shirakyan’s description.

Preparation of punishment

Arshavir Shirakyan was born on January 1, 1900 in Constantinople. He performed the act of punishing Vahe Ihsan on March 27, 1920, at the age of 20. Presenting Shirakyan’s biography with due propriety and respect requires extensive reference. This work has already been done by many researchers and those who knew him personally, and it is presented in his memoirs. Those interested can easily access it on the Internet. There is no need to present the details of Arshavir Shirakyan’s biography here. We aim to present the details of the operation to punish Vahe Ihsan.

Since Vahe Ihsan was on the list of persons subject to punishment by Operation Nemesis, he was followed everywhere. Before that, several Armenian spies-betrayers had already received their long-deserved punishment by other avengers, for example, Mukhtar Harutyun Mkrtchyan, who compiled the list of Armenian intellectuals and handed it over to the Turkish police, Hmayak Aramyants, a Hnchak party figure and writer, and others. Vahe Ihsan knew he was being watched; he understood what it meant well, so he was cautious.

Shirakyan describes a characteristic episode of Ihsan’s level of caution and cunningness. While drinking coffee in a cafe and pretending to read a newspaper, he makes a small hole in the newspaper with a lit cigarette and watches the events around him through that hole. Noticing that a young man is closely following him, he leaves the cafe and brings a policeman who arrests that young man. Because of this incident, the task of following him is taken away from those young people and given to Arshavir Shirakyan. For Vahe Ihsan’s protection, he even had a Turkish policeman attached to him who was always with him.

The punishment

According to Shirakyan, the fact that Vahe Ihsan was still alive after committing so many evils was a reproach for any Armenian young person with a bit of dignity. Indeed, this conviction was the reason why he asked to be assigned the task of punishing Vahe Ihsan. It was decided to carry out the operation on March 27, 1920. During the operation, Shirakyan was accompanied by Arshak Yezdanyan (Musheghyan), known as Yezit Arshak. The latter’s role was to follow the course of events and, if necessary, also help Shirakyan. Yezit Arshak had already carried out the murder of Hmayak Aramyants, a traitorous Armenian, Hnchak party figure and writer.

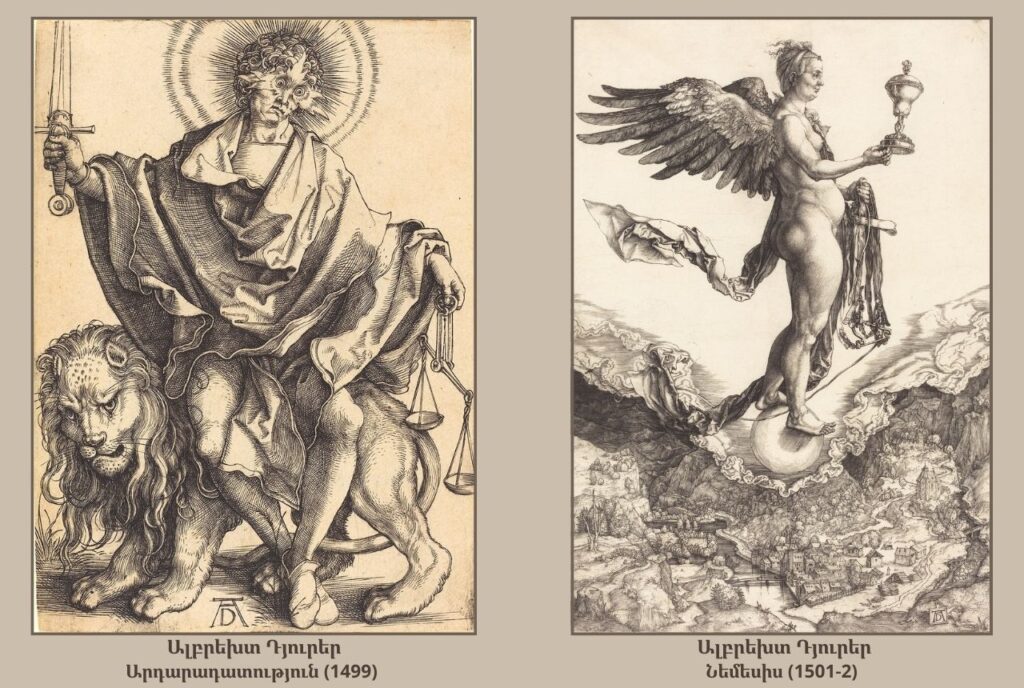

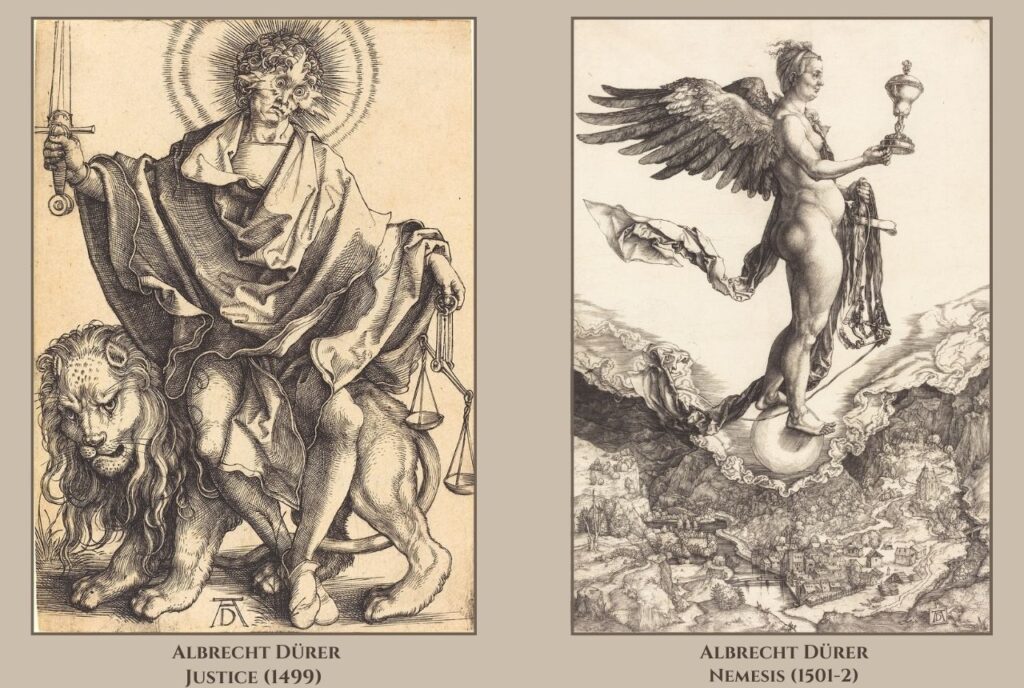

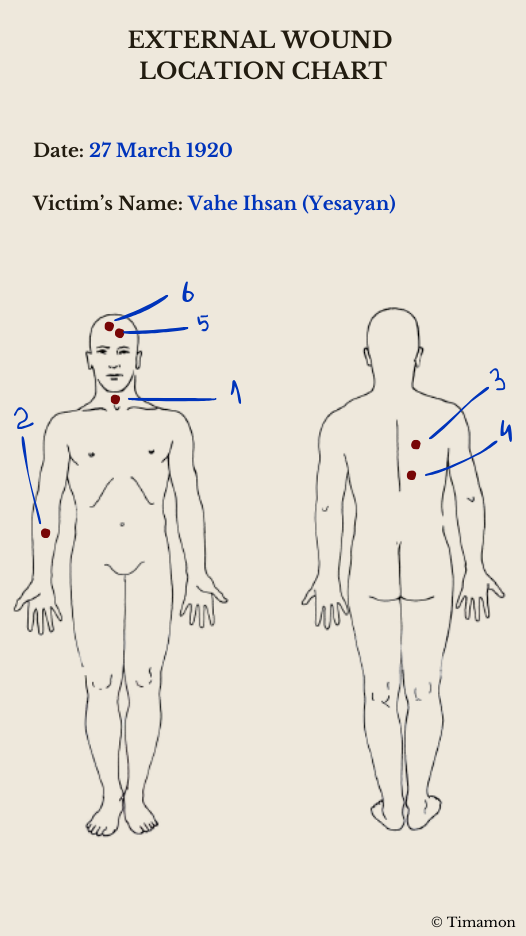

An example of a real diagram used by police in many Western countries (especially the USA) is attached to the description of the punishment. Such documents reflect the location of gunshot wounds on the victim’s body as a result of external examination by forensic specialists. The primary purpose of this document is to give the investigators, the prosecutor and especially the court an opportunity to clearly see what injuries were present on the victim’s body. In our case, too, such a diagram gives an opportunity to clearly visualise the location of gunshot wounds on Vahe Ihsan’s body immediately after he was killed. Shirakyan’s description of the murder of Vahe Ihsan was taken as the basis for the diagram.

On the morning of March 27, 1920, when Shirakyan was walking up the street, he saw Vahe Ihsan coming from the front with his hands in his pockets. Shirakyan knew that he always kept a loaded gun in his pocket. At a distance of 10-15 steps, a Turkish policeman was walking behind Vahe Ihsan as a bodyguard. Shirakyan smiled at Vahe Ihsan as one usually does when he sees a familiar person, took his hand out of his pocket, and raised to say hello. Ihsan was forced to do the same and took his hand out of his pocket, leaving the gun there. At that very moment, Shirakyan takes out his gun and shoots. According to Shirakyan, he aimed at the forehead but missed, and the first bullet hit his throat. Ihsan tried to take the gun out of his pocket while asking for help from the passers-by. The bodyguard policeman ran away as soon as he heard the sound of the shot. The second bullet hits Ihsan’s hand. Feeling that he would not be able to take out the gun with his injured hand, he tried to run away. Chasing him, Shirakyan fires two more shots from behind. A commotion started in the street. Although none of the passers-by intervened, some people began throwing vases and various objects from the windows toward Shirakyan, trying to hinder the pursuit of Ihsan. After a short run, Ihsan falls and hits his head on a stone. Although the two bullets fired from behind also hit him, they were not fatal as well because he unsuccessfully tried to stand up.

Taking advantage of the situation, Ihsan managed to pull out the gun from his pocket and point it at Shirakyan. Without giving Ihsan time to shoot, Shirakyan approaches him and shoots all the remaining bullets into his head. After a few steps away, he returns to ensure that “the monster is dead”. According to Shirakyan’s memoirs, Ihsan’s skull was crushed, and a part of his brain was spilt out. That was the brain that had been the cause of the suffering and death of many Armenians for years. Making sure that the traitor is dead, Shirakyan reloads the gun so that people do not think that he is unarmed and do not try to catch him. Waving the weapon at the gathered people, he demands to open the way and leaves.

Media response

In the March 30, 1920 issue of the “Chakatamart” newspaper published in Constantinople, there was a reference to the murder of Vahe Ihsan. In that reference, there are several essential details about Vahe Ihsan. First of all, it is mentioned that the murdered person is an Armenian named Vahe Ihsan, who was a police official. According to the newspaper, the motive for the murder is most likely revenge because the murdered person used his official position and influence to cause great harm to his Armenian compatriots. The newspaper states that 6 bullets were fired at Vahe Ihsan. The Turkish police allocated more than 100 gold coins to the family of Vahe Ihsan, who died in the line of duty. The newspaper, obviously well aware of all the details of the case, concludes its review of Vahe Ihsan’s murder with the following profound formulation, which remains relevant up to this date and contains a message for future generations: “But what is remarkable in this case is the little sympathy enjoyed by the cash cows in Istanbul. A warning to those who were cash cows.” We think it is clear who the newspaper refers to when it uses the phrase “cash cows.”

According to the newspaper, Vahe Ihsan was married with a 20-year-old son and two minor daughters. The fact that he had three children at the time of his death makes it entirely possible that the descendants of Vahe Ihsan are still living near us, possibly in Turkey or Europe, maybe also in Armenia. Of course, descendants cannot be held responsible for the actions of their great-grandfathers. However, it will undoubtedly be difficult to carry the burden of knowing that your Armenian great-grandfather was on the list, alongside Talaat Pasha, of individuals to be punished for the Armenian Genocide.

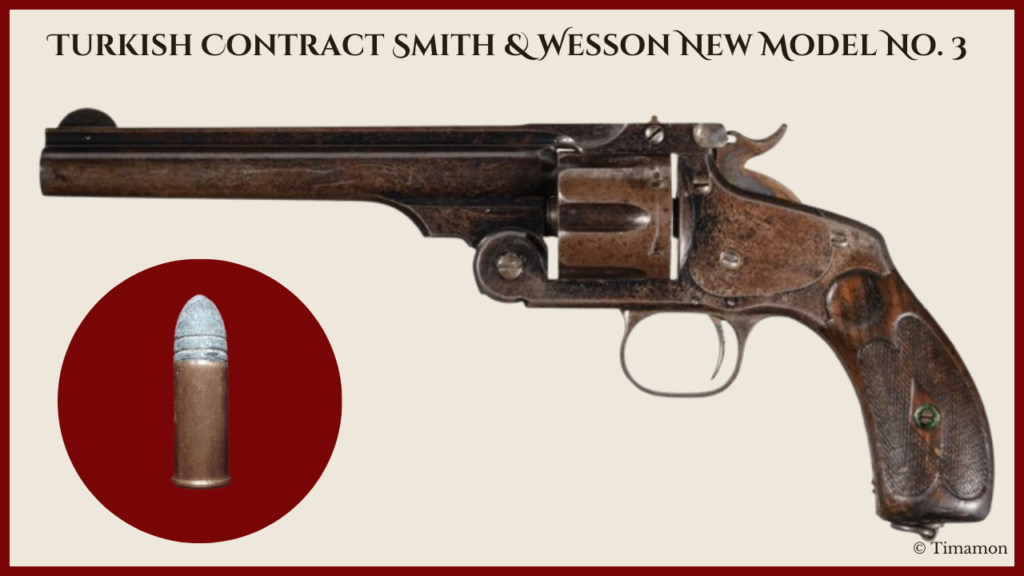

The weapon of punishment

Since in his memoirs, Shirakyan does not mention what weapon he used when killing Vahe Ihsan; we will try to draw a conclusion about the type of probable weapon based on the information he provided. According to Shirakyan’s description and also according to the data of “Chakatamart” newspaper, he shot Vahe Ihsan 6 times, after which the bullets in the gun ran out. To determine the likely type of gun used, we take the guns used by the Ottoman army during the First World War as a basis. There is a high probability that Shirakyan used one of the pistols of these models because they were the ones that were easy to get in the territory of Turkey at that time. As Shirakyan himself mentioned on another occasion, they were able to buy weapons by bribing the Turkish soldiers. It is obvious that the Turkish soldiers, in their turn, took these weapons out of their army arsenals.

During the First World War, the Ottoman army mainly used 7 types of pistols. However, among them, there is only one with a magazine capacity of 6 bullets. This gun is a Smith & Wesson New Model No. 3 revolver made specifically for the Ottoman Army. More than 10,000 of these guns were delivered to Ottoman Turkey, and it is highly probable that Vahe Ihsan was killed with one of them.

The purpose of presenting the relatives of the victims of the Armenian Genocide, i.e. all of us, with such details of the execution of Vahe Ihsan, is to give an opportunity, at least mentally, to be present at the execution of the sentence, as is done in the case of executions carried out in the United States. This is an attempt not to bring back the victims of the Genocide, which unfortunately is not possible, but to bring ourselves back and continue living.