Operation Nemesis has been the subject of thousands of pages of writing, and more will surely follow. Many of its events have been thoroughly analyzed and recounted, while some details remain less known to the public. There are still episodes that have not been fully revealed and await further exploration. Songs and poems have been composed, statues have been erected, and streets have been named after Operation Nemesis and its participants. However, more than a hundred years after Operation Nemesis, we haven’t asked ourselves some important questions and struggled to find answers to our own questions.

What was Operation Nemesis?

What was Operation Nemesis? Was it a convulsive and desperate outburst of a nation that was subjected to genocide, betrayed, abandoned, and pushed to the brink of destruction, or was it a measured response to the terrible crime that was committed against it and went unpunished? Those who characterize the Nemesis Operation as a desperate outburst liken it to an act carried out in a state of extreme emotional disturbance, a “heat of passion” known from criminal law. Of course, it would not be fair to consider Nemesis as an action carried out in the state of collective “heat of passion” of the Armenian people. Any skilled lawyer will confirm that for an action taken under the “heat of passion” it was extremely well-planned and cold-heartedly executed.

It is, therefore, safe to say that it was a measured response to a monstrous crime that went unpunished. Taken separately, it was undoubtedly successful as an action aimed at establishing justice, but why was it left unfinished? Why didn’t it become a policy like the “principle of inevitability of punishment” in criminal law? If the Nemesis operation was accepted by the Armenian people as a new policy, it would be formulated roughly like this: any crime committed against the Armenian people and Armenia, which remains unpunished by the international community, will inevitably be punished by the Armenian people. As a policy, this formulation is morally and legally invulnerable and, most importantly, contains a deterrent element. After all, the most important goal of the principle of the inevitability of punishment is prevention. Its primary purpose is to convincingly show everyone, especially potential criminals, that impunity will not work and sooner or later punishment will come. Adopting such a policy would also send a message to the international community that the crimes committed against us should be punished according to international law by international courts. Otherwise, they will not go unpunished anyway. We would show that we will not tolerate “bargaining” by the international community (or its individual “powerful” representatives) with those who committed crimes against us.

Raphael Lemkin, often referred to as the “father” of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, observed that the Nemesis operation was a calculated response by the Armenian people to the heinous crime committed against them, which went unpunished. In a 1949 interview with CBS, he stated that the failure to punish the perpetrators of the Armenian Genocide led people to “take justice into their own hands,” resulting in the killing of individuals like Talaat Pasha. Lemkin believed that this should not have occurred. He thought that the perpetrators should have been brought to justice through legal and judicial means, rather than by private individuals.

Operation Nemesis – Inevitability of Punishment

Operation Nemesis was an instructive example of the principle of the inevitability of punishment for all. All criminals targeted in the operation were punished publicly in crowded places. No one disputed the fact that they were criminals. The international media wrote about the murder of many of them. It was clear that, even if the international community did not support the actions, they at least recognised that those responsible for heinous crimes received a just punishment.

The practice of publicly punishing criminals dates back thousands of years. In addition to the public display of the inevitability of punishment, it also contains the goal of satisfying the sense of revenge of the whole society, especially of those directly affected by the crime. Public punishment, such as hanging a criminal in the city square, gave the public an opportunity to take revenge on the criminal. Witnessing the criminal’s suffering and public humiliation, society felt satisfied that the crime was punished and assured that the victims received redress.

Sin or justice?

On the other hand, we should remember that Christianity has a highly negative attitude towards revenge. In the Old Testament, revenge was considered acceptable if it was carried out within the framework of the defined “formula”, that is “Eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe” (Exodus 21:24-25). However, in the New Testament, the Old Testament’s “proportional” formula of revenge has been radically revised, and perhaps the most famous wording regarding the inadmissibility of revenge has been given, thus essentially making revenge a sin: “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloke also” (Matthew 5: 38-40).

The Christian church, as well as the State, try in every possible way to prevent us from even thinking about revenge, one urging us to leave it to God and the other to the state system. But we humans have not lost our sense of revenge over the millennia. We often think and sometimes dream about it. It’s not going anywhere. Despite biblical and legislative millennial appeals, we are not becoming more “civilised.” We fail to learn not to resist the evildoer as the Bible teaches us to do. We cannot sit quietly and wait for when and how God or the State will punish those who have done evil to us. Western, that is, Christian civilisation, has done serious work to make the idea of revenge as rejectable as possible. Basically, making the argument that revenge itself is an immoral feeling because it is based on hatred. It is characterised as taking pleasure in the suffering of another, which cannot be considered moral. However, aren’t there people who objectively deserve suffering due to the severity of their crimes? And shouldn’t we approach it with the understanding that others, especially the victims of their crimes or the relatives of the victims, have the moral right, if not to enjoy their suffering, then at least to consider that suffering fair? This is where the concepts of “revenge” and “justice” intersect, and sometimes it is difficult to distinguish one from the other. It is clear that the following formula applies: the state, within the limits of law, tries to satisfy society’s feeling of revenge as much as possible and calls on society to accommodate their feeling of revenge as much as possible within the legal framework of justice.

After reading this story, try to answer the question for yourself: is it revenge or justice? Plutarch, in his work “Parallel Lives,” tells an episode about the life of Julius Caesar. 25-year-old Caesar was captured by pirates while sailing in the Aegean Sea. First, he asks the pirates how much ransom they demanded for him, and when he learns that they demanded 20 talents, he is upset that they demanded such a small amount, proposing to demand 50 talents. He sends his escorts to bring the money and threatens the pirates that if he is released, he will indiscriminately crucify everyone. Obviously, the pirates did not take this threat seriously. After paying the ransom and being released, Caesar, despite not holding any government or military office at the time, gathers a navy, pursues the pirates, captures them, and, as he promised, crucifies them all. If what Caesar did in this story was justice, it was very much like revenge, and on the contrary, if we think it was revenge, it was too close to justice.

In this context, “revenge” should be understood as a retaliation carried out by the direct victim of the crime or his close relatives against the person who committed the crime. In all cases, when the target of revenge is the relatives of the person who committed the crime, his compatriots or, in general, anyone other than the person who committed the crime, then we are dealing not with revenge but with a new indeed no less serious crime committed in response to the original crime.

Revenge and the Social Contract

It is known that in order to create a civilized state, the members of the society have given up some of their rights to the state according to the “social contract”. The right to use force against another member of society occupies an important place in the list of these ceded rights. By ceding this right to the state, we, as members of a civilised society, have given the state’s law enforcement system a monopoly on using force. People have not given up their natural right to revenge because they have decided not to take revenge anymore. They simply transferred the right (and duty) to revenge for the crime committed against them. They delegated to the state the task of seeking retribution within the boundaries of the law in a legitimate manner. In all cases, when the state is unable or unwilling to fulfil this duty of taking revenge, it essentially violates the social contract entered into with society. It is in such cases, when the state or the international community does not fulfil its obligation under the social contract and leaves the crime unpunished, that the natural feeling or, if you will, the instinct to take revenge, to establish justice, to restore the stolen dignity, to clean the stigma of being a victim, is awakened in the people. Of course, revenge doesn’t bring the victims back, but it does bring us back. This mission to bring us back was attempted in Operation Nemesis, and Raphael Lemkin also understood this.

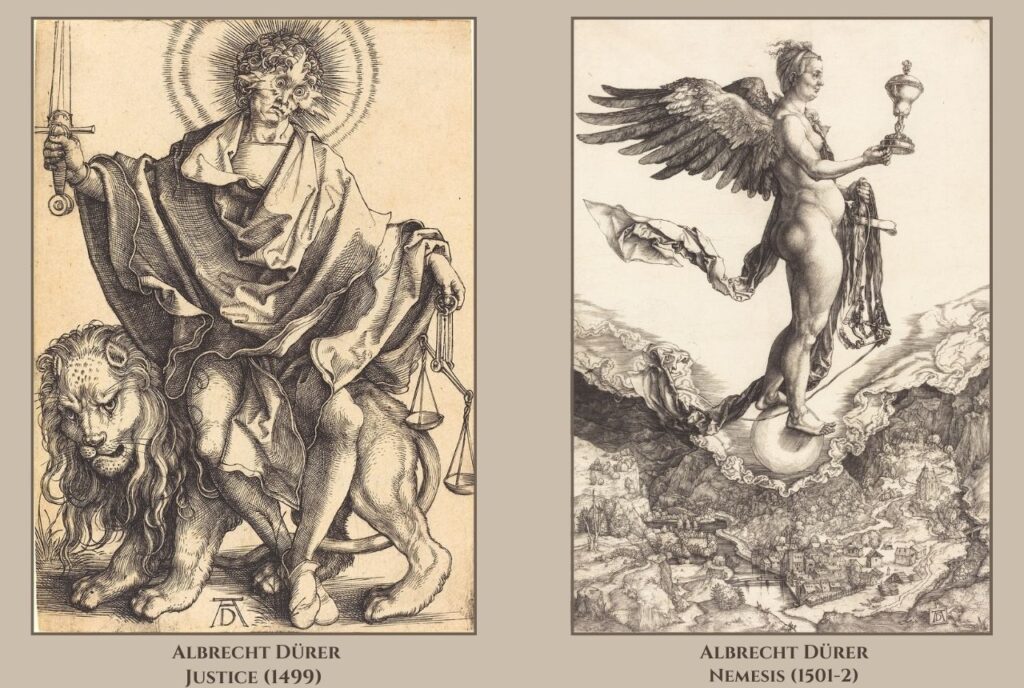

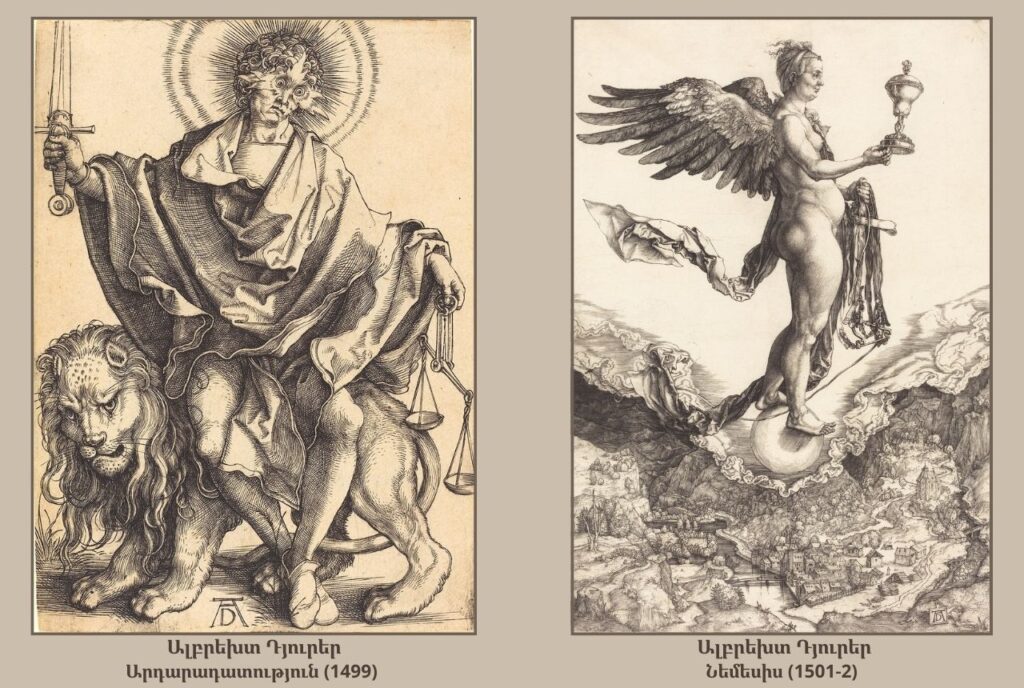

Goddess Nemesis

It should be noted that the operation’s name is highly symbolic and contains a message for the future, which will be discussed later. Nemesis is a Greek goddess who embodies vengeance and punishment. She is responsible for bringing grave sins that go unpunished to a fitting and severe punishment. The goddess Nemesis severely punishes especially unpunished hubris, which is the deliberate use of violence to humiliate the victim, which the perpetrator takes pleasure in. According to Greek mythology, the perpetrator of such a crime violates the rules set by the gods, for which he is severely punished by the goddess Nemesis. However, it should also be noted that the “responsibilities” of goddess Nemesis are not limited to punishing hubris; she is also responsible for punishing those who enjoy a happy or prosperous life without deserving it. Essentially, the goddess Nemesis is responsible for maintaining balance in society. No serious criminal should go unpunished, and no one should be unfairly favoured by fortune. The latter surely also includes the inadmissibility of enjoying the material goods obtained as a result of the crime committed.Notably, the statue of the goddess Nemesis, dating back to the 2nd millennium BC, kept in the Louvre Museum, has a wheel in her hand, symbolizing changeable fortune. The goddess had to turn the wheel of fortune for those who did not deserve that fortune.

Public execution of punishment

It has been more than a century since Nemesis. We have gathered some information about the planning and execution of this operation; some details will be revealed later, while others will remain unknown forever. The information available allows us to address an important topic: how the act of punishing the criminals was carried out. As already mentioned, the public execution of the punishment is necessary, first of all, for the victims and the society in the sense that they are able to make sure that justice has been done and their revenge has been taken. Public punishment is not just criminals burned at the stake, beheaded or hanged in the medieval town square. Today’s public trials and journalists’ reports from the courtroom are also elements of public punishment. Through them, society and the victim’s relatives see the implemented justice with their own eyes, and if they consider it fair, they consider their revenge taken.

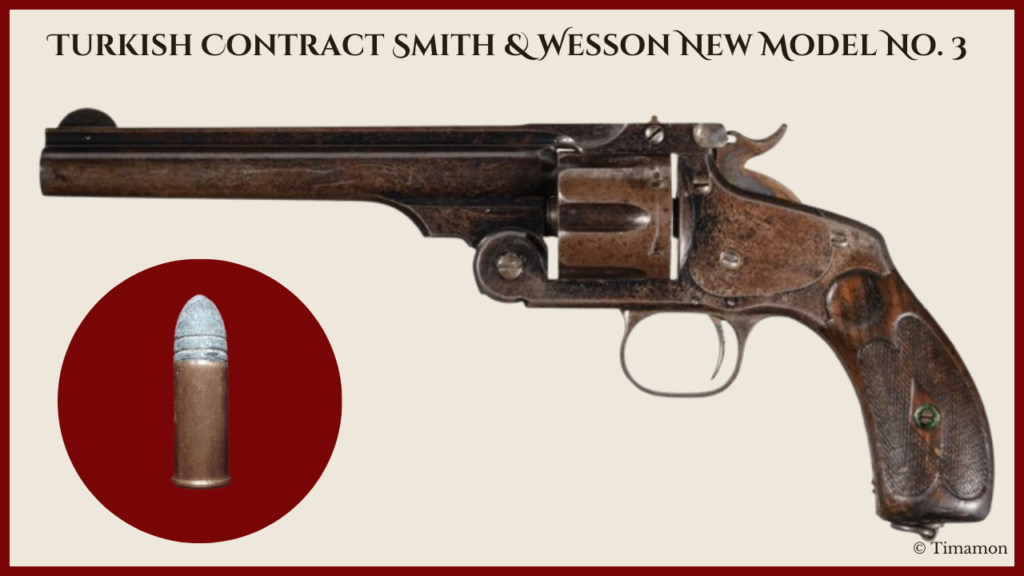

In the case of Operation Nemesis, we know that several criminals were punished. However, we have not seen the just punishment with our own eyes. Therefore, justice done to the given persons did not materialise for us. We have not mentally imagined how this or that criminal was actually punished, where, with what weapon, and under what conditions. Having information about the punishment with such details makes it possible to consider the issue of justice closed, at least for that person, and move on. Otherwise, the crime, even if committed more than a century ago, does not leave the victim alone. Crime that goes unpunished keeps the victim’s descendants as victims and the perpetrator’s descendants as criminals.

53 of the 193 UN member states have the death penalty. The last public execution in the United States was carried out in 1936, which caused great interest among those who wanted to see a public hanging in the state of Kentucky. Even though public executions are no longer carried out in the United States, relatives of the victim have the right to be present in executions carried out inside prison walls. They have the opportunity to witness the entire process of carrying out a death sentence and to hear the convict’s final words, sometimes apologetic and sometimes filled with curses.

In the case of Nemesis, we have not seen the actual execution of the sentences, as the relatives of the victims have the opportunity to do so in the United States. For this reason, we will try to present the details of executing the punishment of the criminals killed during the Nemesis Operation. The goal is to give the relatives of the victims of the Armenian Genocide, that is, all of us, the opportunity to at least mentally be present in the execution of the sentence, as it is done in the United States and be able to move on. With this, an attempt will be made not to bring back the victims of the Genocide, which unfortunately is not possible, but to bring ourselves back.